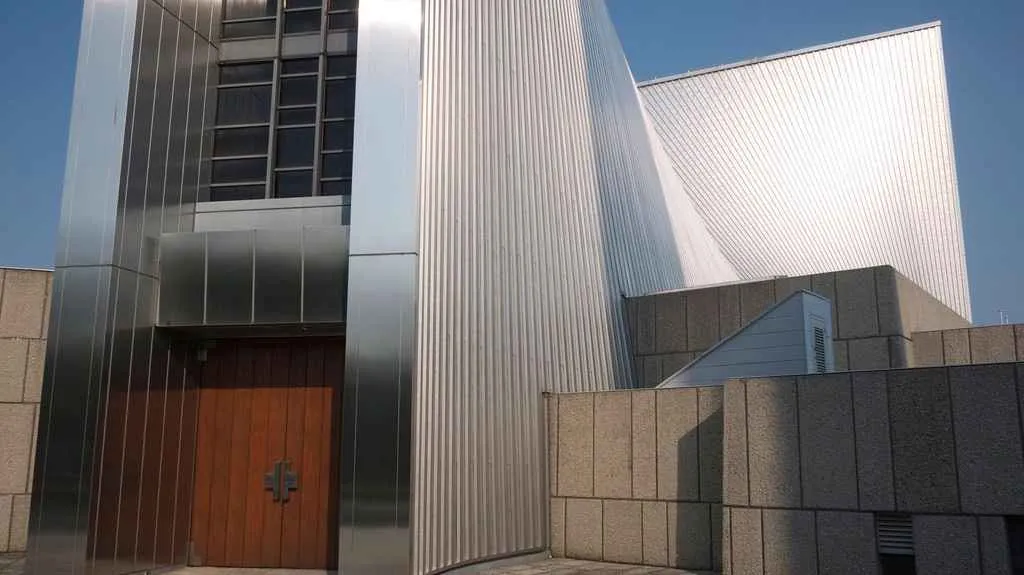

Climbing a gentle hill along Mejiro-dori from the Kanda-gawa area, a gleaming silver structure suddenly appears amid the quiet residential landscape. The solemn atmosphere that surrounds it sets it apart instantly: this is the Cathedral of St. Mary of Tokyo (東京カテドラル聖マリア大聖堂), the main church of the Catholic Archdiocese of Tokyo.

Architectural design and spiritual symbolism

Architecturally, the cathedral stands out for its stainless steel exterior, its sweeping curves shaped from twisted straight lines, and its structure known as an HP shell (hyperbolic paraboloid). This type of construction, adopted globally after World War II, represents a seamless integration of form, structure, and symbolism.

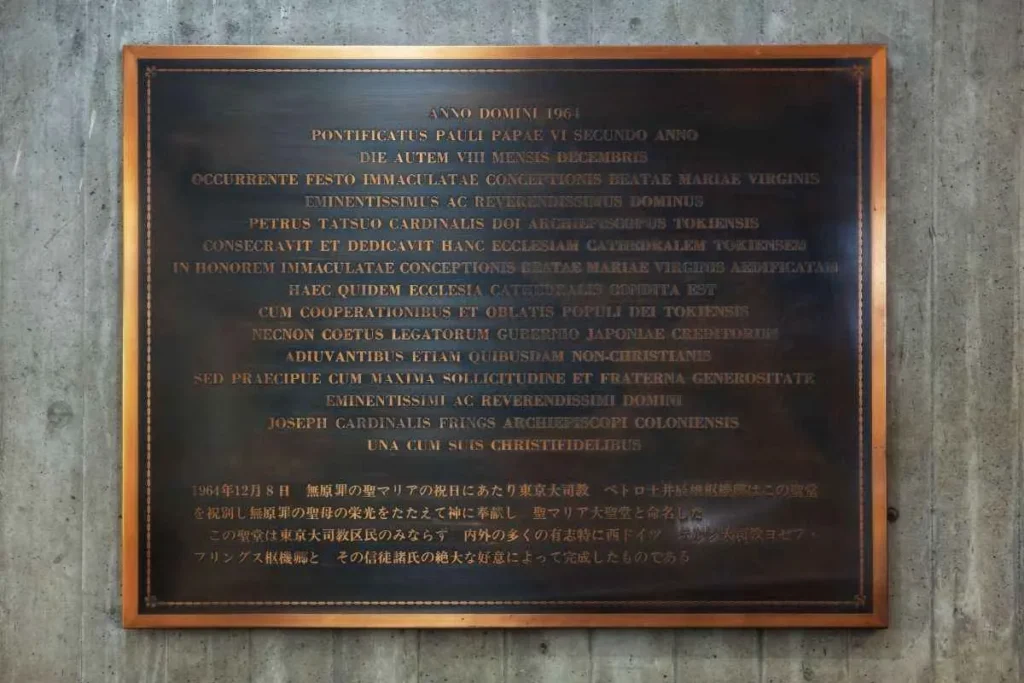

In the late 19th century, French missionary Marie Joseph purchased the land and, in 1899, built a wooden Gothic-style chapel. It withstood the 1923 earthquake but was destroyed by fire during a bombing in 1945. Years later, with support from the Archdiocese of Cologne, Tokyo decided to build a new cathedral. The commission went to Kenzo Tange, who proposed a bold and modern design: a curved, silver structure that looked less like a church and more like a swan preparing to take flight.

The building was completed in 1964—the same year as the Tokyo Olympic Games. Coincidentally, Tange was also responsible for designing the Yoyogi National Gymnasium, a project of national scale. Working on two such monumental projects at once reflected his pioneering approach to collaborative design, which we’ll explore later.

Interior and spiritual experience

Inside, the cathedral features an open and solemn space lined with exposed concrete. The 12 cm-thick curved concrete walls rise gently and meet at a skylight shaped like a cross, allowing natural light to pour in and shift the atmosphere throughout the day. This play of light turns the space into an almost mystical experience, drawing the gaze upward.

Behind the altar, light does not enter through glass but through a panel of alabaster—a translucent stone that emits a warm orange glow—creating harmony between the rough texture of the concrete and the softness of the light.

Symbolism of form and path

Seen from above, the roof clearly reveals the shape of a Latin cross, echoing the design traditions of medieval European churches, such as the cathedral in Pisa. However, the cathedral’s floor plan is diamond-shaped, allowing it to hold more worshippers while visually lifting the cross skyward through its sweeping curves.

Kenzo Tange drew inspiration from Japanese tradition to shape the visitor’s path: instead of placing the main entrance at the front, access is granted by walking around the building, past the bell tower and a prayer space known as Lourdes. This layout, reminiscent of Shinto shrine paths, is designed to prepare visitors emotionally, helping them disconnect from the noise of the outside world.

Traditional elements in a modern language

Tange also incorporated a traditional Japanese architectural feature known as mukuri—a gentle convex curve often found on roofs of shrines and traditional homes. This doesn’t just offer a pleasing visual effect; combined with the metallic surface, it creates shifting shadows that move with the sun.

The freestanding bell tower, standing 60 meters tall, reinforces the church’s Western heritage, while its vertical, curved form echoes the overall design of the temple.

Kenzo Tange’s design method

One key to understanding how Tange managed to design both the cathedral and the Yoyogi Gymnasium at the same time lies in his collective working method. He didn’t design alone—instead, he encouraged his students to present multiple ideas, and through dialogue and discussion, he wove the best elements of each into a coherent final design.

In fact, the Tokyo Cathedral was born from the fusion of two concepts: a cross-shaped floor plan and a form resembling a billowing tent. This collaborative approach helped shape a generation of renowned architects, including Kurokawa, Isozaki, Maki, and Asada.

The man who became one with his creation

Kenzo Tange loved this cathedral. So much so that he was baptized just to be laid to rest within it. In 2005, after his death, his funeral was held here. His ashes lie beneath this very roof, in the crypt.

Today, the Cathedral of St. Mary still stands. Seat of the Archdiocese of Tokyo. Wedding venue. Curiosity for passing tourists. But more than anything, it is a place to pause. To look up. And to feel, if only for a moment, that concrete, too, can be sacred.